Outline History of the British Railway Network

This section provides an overview of the railway system in Britain, general background information on the situation outside the railways fence is contained in Appendix One. A more detailed discussion of the railways locomotives will be found in Appendix Four - Locomotives and DMUs

By the mid 17th Century wagons running on wooden rails were

widely used in British industrial locations (mainly mines), allowing heavy loads to be easily moved

over rough ground.

The early railways of the eighteenth century were all horse-drawn

and were mainly quite short having been built as feeder services for canals and

riverside berths. Up to this point all the railways built had been constructed

by mine owners or other industrial users to move their own goods and although

many of these also carried other peoples goods on a contract basis they were

not obliged to do so by law.

These early lines were often built on

privately owned land (often the 'Estate' of the landowner operating a mine or

quarry) and hence required no special permission to be built and operated. Once

the line extended beyond a private estate however things became more

complicated and the existing legislation for building canals was pressed into

service for railways. This meant that each line had to gain the approval of the

government and obtain an Act of Parliament authorising its construction and

operation. The passing of an Act makes the railway company a 'statutory'

company (which does not have the word Limited after its name) and allows the

compulsory purchase of land.

Most early lines were built with a specific

traffic in mind, stone and lime from quarries and lines feeding iron works were

both common. The first railway built under such an Act of Parliament was the

Middleton Railway of 1758, running between a colliery at Middleton and the town

of Leeds. This line was subsequently one of the first to use steam locomotives

and one section is now a preserved line and still operating with steam

locomotives. The West Somerset Mineral Railway was built to carry iron ore and

the Furzebrook Railway in Dorset was used to move 'ball clay' to the coast for

shipping to the Potteries, in general however coal traffic soon dominated the

scene.

The first truly public railway, on which the right of anyone to

send goods was enshrined in the Act of Parliament authorising the line, was the

Surrey Iron Railway of 1803, engineered by one of the great railway pioneers

William Jessop (see App One - Outside the Fence - Significant engineers and Inventors). This was the first true 'railway company' in the

world, and the first railway south of the Thames in Britain, it ran from

Merstham via Croydon to Wandsworth in Surrey and all traffic was hauled by

horses. In the event this line suffered from competition from new canals built

nearby and it ceased operating in 1848.

These horse drawn lines gave

useful service but there was a limit to the load a horse-drawn system could

carry. A typical 'train' moved between two and twenty tons at a speed of about

four miles per hour. In the period of economic recession following the

Napoleonic Wars and the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo the cost of fodder for

horses had risen prompting greater interest in alternatives to horse power.

High pressure stationary steam engines had been pioneered by William

Murdock in the late eighteenth century and developed by Richard Trevethick in

the first years of the nineteenth century. These could be mounted beside the

track and were used to pull wagons up inclines and even along level ground

using ropes. Some of these hope hauled lines stretched over considerable

distances. The Cromford & High Peak Railway (the first true trans-pennine

railway line, fully opened in 1831) used stationary engines to operate the many

steep inclines with horses pulling wagons along the flat bits. This line was

leased by the London & North Western Railway from 1861 and taken over by

that company in 1887. The LNWR improved the line and introduced steam

locomotives for haulage on the level sections. The LNWR closed several inclined

sections of the line but the remaining incline at Middleton with its steam beam

engine remained rope-hauled until 1963. Once the incline was closed the

remaining level sections remained operational until 1967. If the line was short

with no curves a capstan could be mounted at the top of the incline and a

simple rope loop arranged so that the weight of the loaded wagons going down

could be used to pull the empty wagons up. If the loaded wagons were going up

hill (not common as most such lines were built from a mine to take goods to a

canal or river berth) tank wagons could be filled with water to act as the

counterweight. The loaded tanks would be added to the rake of empties (usually

no more than four wagons at a time) with empty tanks added to the rake of

loaded wagons. This did require a steady supply of water however and the

practice was not common. A more likely reason for seeing water tanks on an

incline would be to supply water to the boiler for the hoisting engine.

Some inclines would be too steep, railway stock is designed to be hauled along the flat not lifted using its couplings. The solution was to build a steep incline carrying transporter wagons built to run on the steep slope. Ordinary wagons can then be loaded onto the incline trucks, however this approach was rare and is associated with industrial lines. The example shown below is at a slate quarry in Wales on which the trolley loaded with loaded slate wagons lifts the trolley loaded with the empties.

Fig___ Steep incline in a slate quarry

Photo taken in 2006 at a preserved slate quarry in North Wales, courtesy and copyright Brian Davies.

There

have been a number of examples of working rope-hauled inclines built in OO and

even some in N. Modelling a steam powered or gravity operated

rope-hauled incline in British N is complicated by the lack of a suitable

'rope', even in 4mm/foot it is difficult to find a suitably flexible thread

although nylon fishing line can be used. One option is to have the incline

disappear into a cutting, allowing straight lengths of wire to be used for the

'ropes'. A simple L shaped hook on the wire would engage the standard N

coupling hook, given a small 'pit' at the bottom of the slope this would

automatically disengage as the rake of wagons reached the bottom of the

incline. For gravity operated lines the two wires (up and down) need not be

linked as the wagons could be assumed to pass each other some way up the hill

and out of sight. This arrangement would allow wagons to be delivered and

collected via a siding linking the main line and the incline with no need to

model the associated industry.

An alternative to horse or cable

haulage on inclined track, where the flow of loaded wagons was downhill, was to

allow the loaded wagons ran down the line by gravity, their speed controlled by

a man riding on one of the wagons and operating a brake. On longer lines horses

were carried downhill in special wagons called 'dandy carts' to pull the train

back up the hill after unloading. The Welsh slate lines were rather fond of

this system of gravity working and it was 1863 before the first steam

locomotives appeared on the Ffestiniog Railway. A few gravity operated lines,

complete with the 'dandy cart' for the horse remained in operation into the

1930's. Unfortunately you cannot 'scale' gravity and making a working

horse is somewhat difficult, I do not know of any layout where empty wagons are

allowed to roll down hill in this way.

A related issue for modellers is

the gradient when changing from one level to another, such as raising one track

to pass over another. A gradient of 1:30 is about the maximum one should allow,

otherwise the engines will experience great difficulty in hauling anything up

the hill. One way of reducing the gradient involved is to lower one track as

the other rises, halving the gradient required. Even so an actual gradient of

1:30 remains very steep even for a model railway, 1:50 is preferable if you

have the room.

On the main lines in Britain where the gradient was steeper than

about 1:50 it was common practice to station an engine near the foot of the

hill to help by pushing from behind. As these engines were not coupled to the

train they could slow down and return to their post once the train had safely

reached the top of the hill. The engines used for this work were called

'Banking Engines'. The Lickey incline on the former Midland Railway line in

Worcestershire is I believe the steepest main line gradient in the UK, at about

1:38. The MR used tank engines for a time but then built a single heavy 0-10-0 loco

for the work (they built a spare boiler for this engine to reduce the 'down time' in the event of any problems).

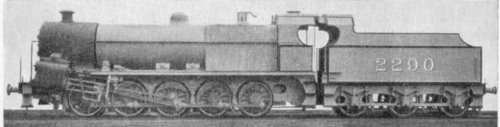

Fig___ The classic banking engine in LMS livery

More recently, even with the more powerful modern locomotives,

diesel engines have performed banking duties on this line.

When coming down the

gradient it was sometimes considered sensible to put the banking engine at the

front of the train to add its braking power, also in the days of unfitted stock

all the wagons had to have their brakes pinned down to prevent them running

away. This was usually done as the train was drawn slowly past a shunter

standing beside the track at the top of the hill. On quieter lines the guard

performed this duty, the train being brought to a stop to allow him to do the

job, and halted again at the bottom of the hill to allow him to return the

brakes to the off position. These complications and delays were one of the

reasons railways went to great lengths to find level routes for their lines.

By the early nineteenth century railways had proved themselves for

industrial uses and there were several quite lengthy lines in operation, mostly

horse hauled. Steam locomotives were in use on some lines, most associated

with collieries or iron works where fuel was plentiful, but the technology was

still in its infancy. In spite of the problems with poor roads and over crowded

canals many people had grave doubts about the value of steam locomotives.

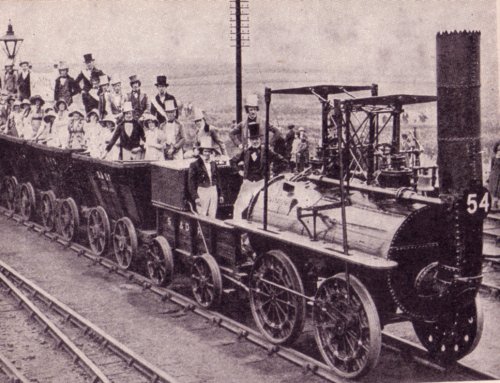

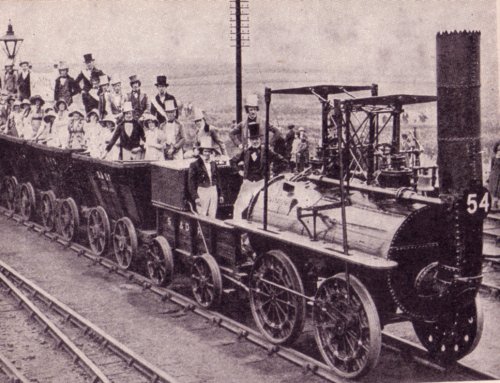

An early success was Locomotion No.1, built by George Stephensoon for the Stockton and Darlington line opened in 1825, this used a moderately high pressure boiler driving the pistons in vertically mounted cylinders with cross beams driving the wheels using coupling rods. The photo below was scanned from a book published in the 1930s, the photo was taken at the Centenary exhibition on the line in 1925 and shows a replica engine built for the occasion which proved capable of speeds of up to 12 miles per hour when pulling a full load. The telegraph pole with its bank of insulators would not have been present when the original engine was in service.

Locomotion No.1 replica on the Stockton and Darlington line

The catalyst for change was the building of the Liverpool &

Manchester Railway, intended to carry the raw cotton imported at Liverpool to

the water powered mills around Manchester. The building of this line required

an Act of Parliament and parliament was dominated by the conflicting interests

of various pressure groups. The British democratic political system was still

in its infancy, few people had the vote and rioting was not uncommon as a

method of protest. The Duke of Wellington was Prime Minister at the time and he

was generally opposed the building of railways as he felt it was politically

dangerous to enable large numbers of people to move about the country.

Rope haulage using large stationary steam engines beside the track was

seriously considered for the Liverpool & Manchester line however George

Stephenson (1781-1848), a respected railway engineer and a believer in the

steam locomotive, was hired as the Liverpool & Manchester Railway Company

chief engineer. Once the decision was taken to consider using steam locomotives

on at least part of the line the parliamentary debates on the Liverpool and

Manchester line became even more heated. Existing steam locomotives were

inefficient, using a lot of coal and producing a lot of smoke and soot which

people believed would poison the land and cause cows to stop giving milk. The

first attempt to obtain an Act for the Liverpool to Manchester line failed

largely because a certain Duke thought the line would upset his fox hunting

(research in the 1940's showed that a steam railway actually had less impact on

wildlife than a well used footpath).

Respected scientists testified

that people would be unable to breath at the high speeds (perhaps more than

thirty miles per hour) suggested by the engineers. Partly due to Stephenson's

enthusiasm for steam locomotives the Liverpool and Manchester Railway company

staged a series of competitive engine trials at Rainhill in 1829. One entry was

horse powered and another was operated by two men and a hand-crank but all the

rest were all variations on the new steam locomotives of the time.

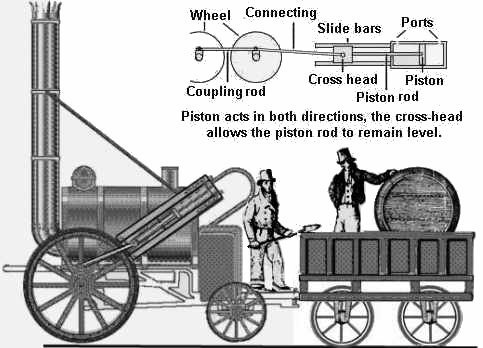

It

was for this competition that the famous locomotive Rocket was built by George

Stephenson's son Robert Stephenson. The Rocket featured efficient cylinders (made using a recently developed boring technology) and

a multi-tube boiler that increased the heating area dramatically, it won the trials and demonstrated the potential power of steam locomotives.

Fig___ The Rocket of 1830

Essentially similar locomotives were ordered by the

railway company, which opened for passenger traffic in September 1830 as the

first all-steam hauled passenger and general goods railway and also the first

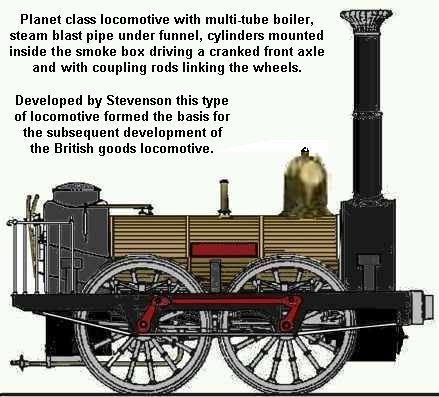

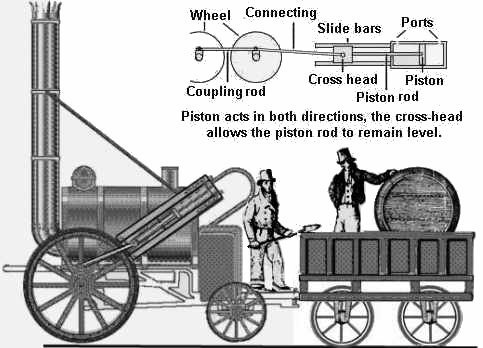

inter-city line in the world. Very quickly an 0-4-0 wheel arrangement was adopted (notably for freight engines) providing greater traction although with a lower top speed.

Fig___ Early 0-4-0 freight locomotive

The Liverpool & Manchester Railway company

introduced the double-track which is so characteristic of British lines and

arguably more than any other encouraged experiment and so facilitated the rapid

development of railway systems.

The line was actually

built to transport the thousands of tons of materials shipped each year from

the port of Liverpool to the mills and factories of Manchester. The first goods

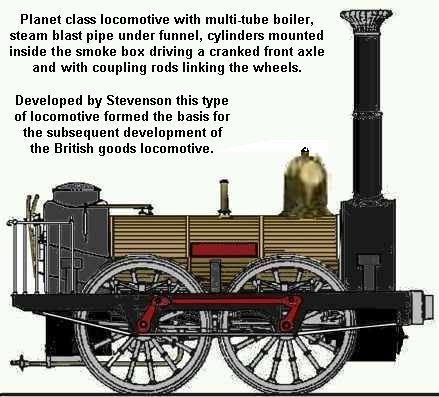

train passed down the L&M line in December of 1830, the locomotive 'Planet'

hauling about eighty tons of goods over the thirty one miles (48 km) in less

than three hours. The goods hauled by Planet were bulky and this was the

equivalent of three barge-loads which would have taken 36 hours to complete the

journey. There is a sketch of the Planet in Appendix Four - Locomotives and DMUs - Overview and General Information

The L&M railway lines were soon extended through Liverpool to the

docks and there up to twenty goods trains a day running each way on the line.

Despite the early shortage of locomotives by the mid 1830's there were over two

hundred thousand tons of general goods and a further hundred and some odd

thousand tons of coal being moved on this line each year.

For a sense of the scale of the operation the Manchester Liverpool Road station is described in some detail on the Disused Stations web site. Thanks are due to Dennis Markuss for pointing this out.

Passengers

were expected to be relatively few in number but in the event there were soon

over a thousand passengers a day travelling along the line and that figure had

doubled by the end of 1831. For some time the total money earned from passenger

trains was greater than from goods, although the profit margin on passenger

receipts was smaller than that for goods traffic.

Fig___ 1830s railway booking hall (Manchester)

This unexpected demand for

passenger travel was seen on all the early railways and the prestige due to

popularity of the railways with the travelling public proved to be a benefit

when dealing with parliament.

Within a few years passenger fares

amounted to over two million pounds per year. Goods receipts were more than

twice that figure, and provided a greater return on invested capital, but

drivers of goods and luggage trains were still instructed to leave the line

clear for passenger trains, 'by shunting if necessary'.

The Liverpool

& Manchester railway company built up a stock of about 400 wagons in

addition to which various users operated privately owned stock. The single

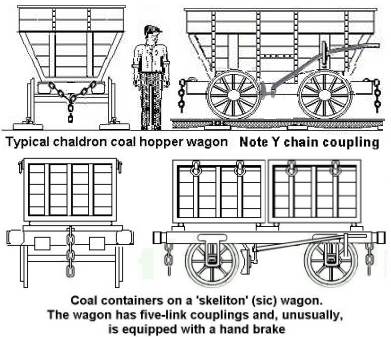

largest contribution to goods tonnage was naturally coal, at the Manchester end

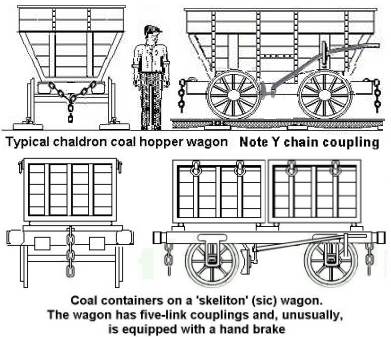

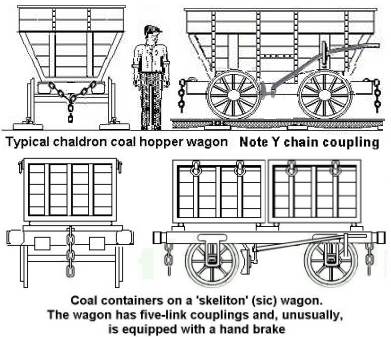

of the line bottom-discharging hopper wagons of the chauldron type were used

emptying into excavated drops. The Chaldron is a measure not a weight, corresponding to 36 bushels, 864 gallons, 139 cu feet or just under 4 cu metres, and equates to roughly three tons of coal. The chauldron was the legal limit for horse drawn coal road waggons heading for London as it was felt that heavier loads would cause too much damage to the roads. The railway chauldron wagons were about ten feet long and about six feet three inches high and featured a very short wheel base ranging from about four feet six inches to about six feet. The short wheelbase, a hangover from their colliery origins, enabled them to be used on extremely tight curves and the same general design

continued in use up to the 1970's on colliery lines in the North East. In

Liverpool wooden coal containers called 'skips' were carried on 'skeliton

wagons' (sic - a simple chassis with no body) and were craned onto road wagons

for delivery. The container wagon has two sets of buffers as the chauldrons buffers were lower down and closer together than on standard rolling stock so some wagons had the extra set to run with them.

Fig___ L&M Rly. 'chauldron and coal container wagons

The coal containers or 'skips' were by no means a new idea even

in 1831, they had been in use in collieries for over a hundred years and the

nearby Bridgwater canal routinely used them for transporting coal in barges.

The coal containers were not a great success on the L & M but proved

popular on other lines and have remained in service in one form or another to

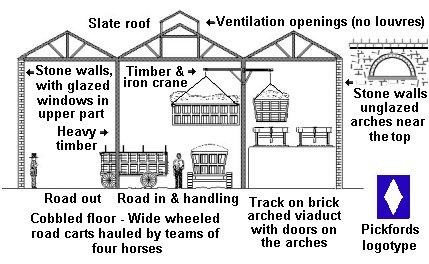

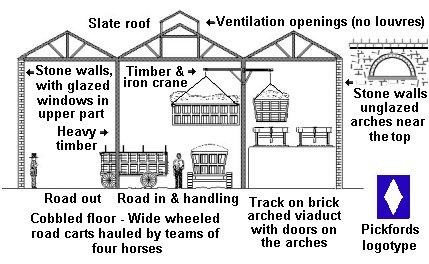

the present day. Pickfords the road haulage contractors built some general

merchandise containers in the early 1830's and these remained in service for

many years. Large purpose-built terminals were provided to transfer these

general merchandise containers from the railway to horse drawn carts.

Pickfords started out in the road

haulage business in a town called Poynton in Cheshire in the 1740's, and were

by this time a well established company. They had moved their headquarters to

London in about 1823 (the last family member connected with the firm died in

1846). As well as road carts and wagons they owned a fleet of canal boats and

it is believed that their logo in this era was a vertical white diamond shape

on a dark blue or black background. This logo was painted on the canal boats

and was probably applied to the containers but I have not managed to find any

illustrations that show its placement.

Fig___ Cross section of

1830's Pickfords container terminal

Container traffic on the railways is

discussed more fully in the section on Unit Loads on the Railways.

Initially railways were seen as being essentially similar to roads and

canals, a 'road' on which independent contractors could haul trains of goods,

and this way of working was not uncommon in the first years of the Nineteenth

Century. Things went fairly well in the era of horse and cable haulage but

after a series of mishaps all locomotive hauled trains had by law to be pulled

by Railway Company locomotives. Private railways such as those operated by

collieries were allowed to operate their own locomotives but these would not be

allowed to venture out onto the railway system proper.

Following the

lead set by the canals ownership of railway goods rolling stock has always been

divided between the railway companies and Private Owners (usually abbreviated

to PO). A few of the early railway companies actually owned no stock at all,

everything being carried in private owner wagons. The Liverpool &

Manchester Railway was initially intended to operate as a 'highway' on which

private contractors could operate their own trains, this state of affairs did

not last for long however and by 1834 the company had bought out all the

private passenger coach operators. This meant that the company had to invest a

lot of capital in the railway rolling stock. Allowing privately owned goods

vehicles meant that other peoples money was used to build and maintain these

and privately owned goods wagons do not incur rental charges for the user. A PO

wagon can therefore serve not only for transport but also for storage on the

users own siding. PO wagons have remained a feature of the British system up to

the present day.

The railway system of charging evolved based on

experience, no one had operated a railway before and the system became ever

more complicated (see also Historical Background - Charging for goods on the

railways).

Goods shipped in

open wagons were subject to weather damage but the high speeds meant this was

less of a problem than with other forms of transport. A new threat however was

fire, the early locomotives used coke rather than coal and the simple boiler

designs meant that sparks and glowing embers were often blown out of the

chimney. The fire grates under the boiler were not enclosed and red hot or

burning embers fell from the simple fire grates onto the track. One early

passenger wrote enthusiastically of being "drawn along as though in the tail of

a comet". A lot of the traffic on the Liverpool & Manchester Railway was

bales of cotton and after several fires the company engineer George Stephenson

advised that heavy canvass should be used to cover all loads for protection.

This did not stop the wagon fires caused by embers on the track being caught up

in the wagon wheels and whirled round but it was a couple of years before all

locomotives were fitted with ash pans. The open wagon with the canvas tarpaulin

cover, or 'tilt' as they were often called, remained the principal method of

goods transport for over a century.

The success of the steam hauled

Liverpool and Manchester Railway prompted the building of new lines around the

country. The Grand Junction Railway opened in 1837, running from Birmingham to

Warrington, where it connected with the Liverpool & Manchester Railway

becoming the first railway trunk route in the world. A year later the London

& Birmingham railway started operations, completing the link to the

capital. The early railways were generally successful, they survived the

industrial depression of the early 1840's and in the following years there was

a boom in railway development, partly encouraged by the fortunes made by the

people who had invested in the early canals and waterways.

By the late

1840's the era of experimentation on the railways was over, the lessons learned

in Britain enabled other countries to build their systems with much less

confusion and trouble. Over the next sixty years virtually all the railways in

the world were built, most using the same gauge track as the Liverpool and

Manchester. The building of the railways around the world was the largest

single task ever undertaken by humanity, the equivalent of building several

thousand copies of the Great Wall of China.

The relative high speed of

the railways allowed perishables to be carried from the country to the large

towns and by the late 1840's London was receiving over seventy tons of fresh

fish a week from the ports of Yarmouth and Lowestoft courtesy of the Eastern

Counties Railway. The railways involvement with the fish trade is discussed in

under Freight Operations in the subsection dealing with Non Passenger Coaching

Stock Operations. Natural materials used for dyes were a profitable cargo for

the railways, imported vegetable matter such as Madders, Indigo and Safflower

were moved in considerable quantities (up to the 1880's when synthetics took

over).

The average length of a British railway company line at this

time was in the region of fifteen miles and it was inevitable that lines began

to consolidate and merge, establishing larger and more efficient companies

covering much larger geographical areas. For example in 1846 the Liverpool

& Manchester, the London & Birmingham, the Grand Junction Railway and

the Manchester & Birmingham amalgamated to become the London & North

Western Railway (LNWR), which thereafter titled itself the 'Premier Line'.

By his time the railways had become a vital part of the nations

economy, fears of the power wielded by the railway companies lead to the

'common carriers' legislation (see also Historical Background - The Common User Scheme) and even calls

for nationalisation of the British network. The railway companies, with the

rather dubious railway magnate George Hudson (1800-1871) as their spokesman,

did not want unrestrained competition which they felt would be ruinous (the

American experience suggested there was truth in this contention). Hudson

pressed for a middle course based on a potentially highly profitable 'regulated

monopoly' and in this he was moderately successful.

In 1844 a separate

Railway Department was formed at the Board of Trade, ostensibly to look at the

relative merits of various proposed railways and mergers of existing lines. In

the event the fear of monopoly meant that a great many railways were built with

little regard for how competition would affect their fortunes and several major

trunk routes were duplicated or even triplicated. In mainland Europe the state

exercised greater control over the railways in order to establish orderly

strategic networks. Belgium, which had gained its independence from Holland in

1830, saw a National Railway as a vital component of its national identity and

the network was sponsored by the government. In France no tracks were laid

until the Government had devised a strategic system based on Paris, in the

1840's four regional companies were established, each with a ninety nine year

lease on their territory and the legislation discouraged competition between

the lines (the four railways were amalgamated in the mid 1930's to form the

national railway operator SNCF). In the fragmented collection of small

semi-independent states that later became Germany there was a real need for a

military strategic railway network and little alternative to State funding.

In Britain the Railway Department of the Board of Trade encouraged the

process of standardisation, mainly with regard to safety systems and signals.

The railway companies were by now very powerful organisations, Parliament at

the time was dominated not by party politics but by interest groups and the

Railways were amongst the most powerful of these. As a result most of the

Railway Departments rules were only applicable to lines and installations built

after the rules were drawn up, few changes were forced to existing systems.

In the 1840's, 50's and 60's there were a series of commissions on the

Railways, all seeking to establish some means of avoiding a monopoly whilst

allowing the railways to work efficiently. One change introduced in the 1850's

was the banning the railways from granting special privileges to individuals (a

method used to 'buy off' the objections of rich land owners and competitors).

In 1867 the Commission on the Railways reported that there were close to two

thousand pieces of legislation now in force relating to railways and another

fifteen hundred or so which contained amendments or modifying clauses. Given

the complexity of this legislation, and the fact that it contained many

contradictions, they concluded it was practically impossible to sort out what

the legal duties and responsibilities of any particular railway might now be.

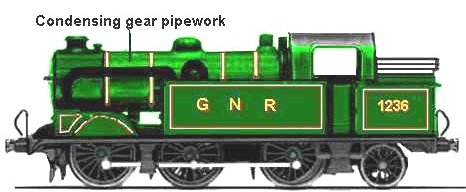

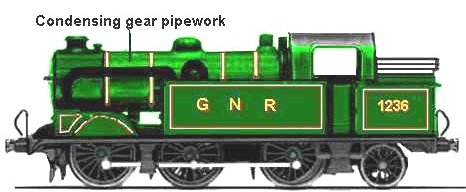

In 1863 the first of the London underground lines opened from

Farringdon to Paddington, this was the worlds first underground railway. The

concept had been championed by a man called Charles Pearson who was Solicitor

for the City of London. Mr Pearson's plan for trains running in drain-like

tubes was ridiculed by Henry Mayhew, the author of The London Poor and the

founder of Punch magazine. Punch ran a series of articles suggesting ways that

various coal cellars and the like might be used as part of the route to save

money.

The line was built and the MP Mr. Gladstone travelled on first

train with his wife but Mr. Pearson had died six months beforehand. In 1863

three quarters of a million people went to work in London and the new

underground railway was to prove a great success. The steam trains represented

a problem when running in long tunnels as the steam and fumes from the boiler

would suffocate the passengers. The original solution was to route the steam

into tanks on the locomotive which could be opened to release the steam as the

train passed under large ventilating openings. A later and more successful

approach was to feed the steam into condensers and return the condensed water

to the boiler feed tank on the engine. The tank engines fitted with this

equipment can be identified as they have large diameter pipes visible on top of

the side mounted water tanks.

Fig___ Underground railway 'condensing' engine

The introduction of the first Bank Holiday in 1871, along with other traditional holidays taken by factory workers, saw an increase in interest in day's away by train, usually to a seaside destination.

The Midland Railway, a late comer in the

railway world, had rather longer routes and had to compete for passengers by

offering greater comfort and amenities. The Midland was noted for its eagerness to promote its lines for tourism. In the 1870's they brought in some

American 'Pullman' coaches, these had no compartments and passengers could move

from one coach to another via the small boarding platforms at the ends. Dining

cars appeared in Britain on the Great Northern Railway in 1879, but these had

no connecting doors so the clientele remained in the coach for the entire

journey or moved when the train stopped at a station.

In 1881 concern

over the spiritual welfare of the railway staff, many of whom spent much of

their time away from home, prompted the formation of the Railway Chaplaincy.

The force behind this was a remarkable lady by the name of Emma Saunders who

had been working to provide the railway staff with moral and social support

since the 1860's. This was a time of increasing interest in evangelical

Christianity and Mrs. Saunders, know by this time as 'the railway mans friend',

gained the backing of Lord Shafstbury, a major force in social reform. The

Railway Chaplains still travel the system today giving spiritual support to

railway personnel and passengers. They can be requested by a particular staff

member at any time and they will travel through the system to meet the person

wherever it is they may be. The Chaplains are interdenominational and are drawn

from many Protestant churches, they do not these days wear the clerical 'dog

collar' but they carry an identity tag on their lapel to identify them to

staff.

In 1884 Gladstone, by now the Minister of Transport, headed a

Select Committee to review the development of the railway system. On the

continent there was much more state involvement and there was talk at the time

of the British government entering into a partnership with the railways (as had

been done in France) or even of complete nationalisation. In the event nothing

much happened at the time. In 1886-87 a Royal Commission on Railways looked at

the question of regulating Britain's railway network again and although

Gladstone's ideas on partial nationalisation were considered they were in the

event rejected. It was decided that a recent law, entitling people to claim

compensation for loss or injury on the railway was sufficient to protect the

interests of the public and that the Board of Trade should not directly

interfere in the running of railway companies.

The 1888 Railway and

Canal Traffic Act represented the growing realisation that the nation's

railways were a strategic and economic asset of unrivalled importance. The

Railway and Canal Commission was made a permanent body and given stronger

powers whilst the Board of Trade was appointed to act as an impartial

arbitrator between the railway companies and people who felt they had a

grievance.

Also in 1888 the first 'slip coaches' appeared on the London

Brighton and South Coast Railway, the South Western Railway and the Great

Western Railway. These coaches had their own brakes and could be detached from

the rear of a train while it was moving, allowing them to be 'dropped off' as

the train passed through a station.

In spite of various accidents

during the 1870's the railway companies had resisted Government attempts to

introduce more sophisticated brakes on passenger trains. This was partly

because of cost but also they were unable to agree on a standard system.

Following a serious accident in Ireland in which 80 people died, many of them

children, automatic continuous brakes became mandatory on passenger stock in

1889. Automatic means that if the train parts the brakes on both sections will

automatically be applied and continuous means that all the vehicles brakes can

be controlled from a single point, usually the engine. Rolling stock equipped

with this kind of brake is usually described as 'fitted', vehicles with only a

hand brake are described as 'unfitted'.

There were many different

designs for brakes (these are discussed in the section on Rolling Stock

Development) in Britain most companies opted for the vacuum operated automatic

brake systems, usually abbreviated to AVB. The use of continuous brakes allows

higher speeds and it was not long before such brakes appeared on high speed

goods stock such as cattle wagons, fruit vans and fish trucks, allowing these

to travel attached to passenger trains. Most goods wagons remained

'unfitted' and goods trains trundled about at 25 to 30 m.p.h.

The first electric trains on the London Underground railway system

appeared on the City & South London Railway of 1890 and the inner London

underground system was fully electrified by 1905.

Fig___ Early London Underground Electric Locomotives

Services in the outer areas

of the system remained steam hauled and some of these steam services lasted

into the British Railways era.

In 1895 an act of parliament allowed the

setting up of 'Light Railways', this was in part an attempt to help the rural

farmers compete in the new national market supplied with cheap imported food.

The light railway was not bound by the same regulations as the larger main line

companies and so cost less to operate, but the speed on such lines was

restricted to a 25 mph (40 kph) and the maximum load was about ten tons per

wagon. Not all light railways were operated by minor companies, some lesser

branch lines of the larger concerns had originally been granted their Act of

Parliament for goods traffic only. Some of these goods-only branches were

granted the right to carry passengers under light railway orders. This means

you can have a branch line on your layout which uses older and lighter

locomotives, older carriages and carries regular goods traffic.

The

last Light Railway to operate in the UK was (I believe) the Derwent Valley

Light Railway which opened in 1913 and closed down in the later 1980's having

remained independent throughout it's existence. There are some useful photos of

this line taken in the 1970's in the book British Railway Goods Wagons in

Colour by Robert Hendry (Midland Publishing ISBN 9781857800944).

Light

Railways generally had lower platforms than the main line companies and some

arranged stops at the level crossings on the line, this was one reason so many

early lines had footboards on their carriages. The larger railways companies

then tried the same idea, fitting local coaches with fold down steps to allow

passengers to board at level crossings. This was not considered a success,

Humphrey Household's book Gloucestershire Railways in the Twenties (published

by Alan Sutton in 1984, ISBN 0862991978) suggests that after trying this

approach on their steam rail-motor coach units in about 1900-1903 the GWR

switched to building short wooden platforms and in so doing introduced the word

Halt to describe them.

It is perhaps worth noting that at the end of

the nineteenth century there were about fifteen hundred miles (2,400 km) of

horse-hauled wagon ways still operating in Britain.

There were a number

of narrow gauge lines in the country, many of which operated as light railways.

The problem faced by these lines was the transhipment of goods to and from

standard gauge stock. One company, the Leek & Manifold Light Railway solved

this problem by building transporter wagons. These had 'foot boards'

to either side fitted with rails to carry standard gauge wagons. The London

& North Western Railway and the Great Western Railway, both of whom

operated services into the slate producing areas of North Wales, built standard

gauge transporter wagons so the loaded narrow gauge slate trucks could be

carried to the docks without transhipment.

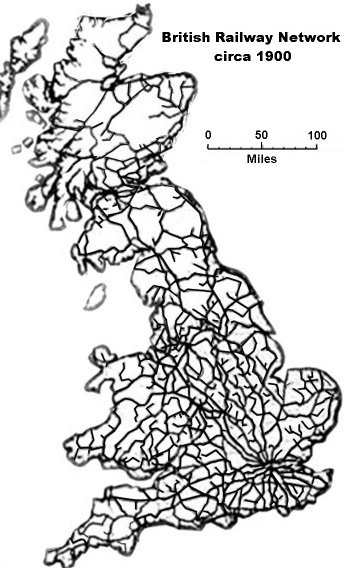

By 1900 the British railway

system was virtually complete, the last major trunk route was the Great

Central's London Extension to the new Marylebone terminus in 1889, but that

venture probably never paid for itself. The Great Central had decided to run

its own line into London having had problems with its running arrangements with

both the LNWR and the GNR for access to the capital, arrangements which had

earned the nickname 'the flirtatious railway'. Closed cabs were standard on new

locomotives, some of the older designs in the ready-to-run ranges date from

this era and other types can be modelled using the Graham Farish 0-6-0 tanks,

and possibly the 4-4-0 tender locomotive as a basis. Bogie coaches started to

appear in the early 1900's but the old four and six wheeled stock continued in

use.

By this time British railways were carrying about five hundred

million tons of coal a year (as opposed to about thirty five million tons in

1995) and the number of passengers carried each year in Britain alone was

roughly equivalent to the then population of the earth. Cattle were a regular

traffic for the railway companies, involving purpose built cattle wagons often

marshaled into an entire train. Milk from the country to the towns and cities

had been moved by rail from the 1870's and soon became a major traffic

flow. Initially the milk was not treated in any way, it was delivered to the

station in silver conical churns and carried in slat sided vans to the towns

(milk tanks appeared in the early 20th century carrying processed milk from

purpose built 'creameries' in the country). Long trains of purpose built fish

wagons and vans were being hauled from the fishing ports to the larger cities

by large express locomotives.

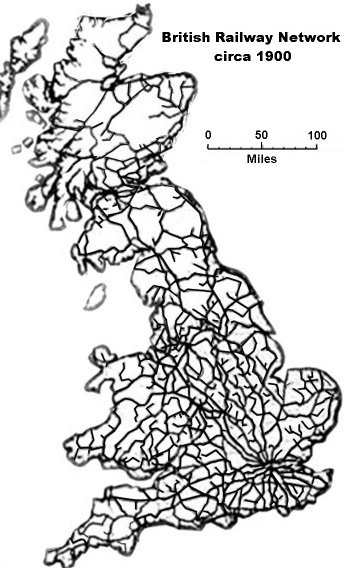

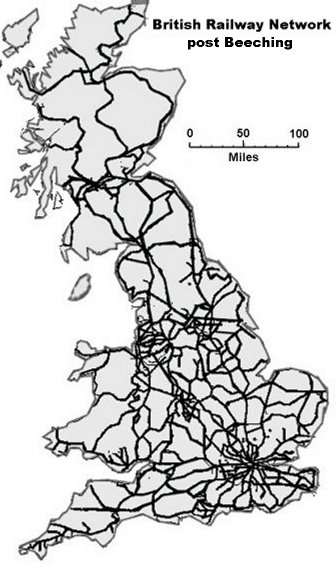

Fig___ British Railway Network

1900

Branch lines continued to be laid into the early twentieth

century but there was very little development of the railway network after

about 1920. By this time the large numbers of petrol lorries, and men trained

to operate them, that had come onto the market after the First World War was

starting to impact on the railway freight business. Similarly motor-buses were

increasingly being used for local passenger transport, although these were less

comfortable than trains they were cheaper.

Click here for some notes on the heating and lighting

used on passenger trains.

In 1903 electrification of some

lines around Tyneside was begun using outside third rail pick-up. In 1904 the

Liverpool to Southport main line became the first British main line railway to

be electrified using an outside third rail carrying 600 volts DC.

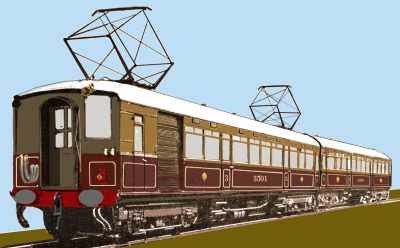

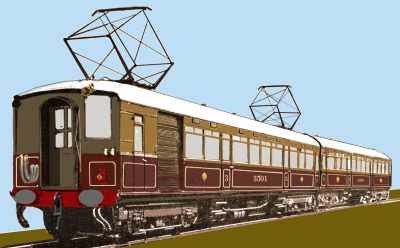

Fig___ 1904 L&Y Railway EMU

Pride

in service and company loyalty were very high amongst railway employees.

'Uniformed' positions meant staff did not have to buy their own working clothes

and it was a steady job which was highly valued. There had been a move toward

improving the lot of the railway employee since the 1890's, the railway workers

were the first men to have their hours regulated by the Board of Trade.

Meanwhile the effect of the continuing competition between companies was an

increase in the amalgamations. The Board of Trade intervened again in 1907 to

avert a strike and set up review boards for pay, but by 1911 a widespread

strike was unavoidable and involved most of the larger companies. This strike

was in part due to unfavourable settlements reached regarding pay and

conditions and partly due to the feeling that railways had always paid poorly

but offered security of employment. The series of amalgamations had lead to a

reduction in staff and even where redundancy did not follow promotion prospects

were blighted.

Express goods trains appeared in the early 1900's,

offering speeds in excess of 40 mph (64 kph). Rolling stock used in such trains

had to be fitted with oil filled axle boxes, at least a third of the wagons had

to be 'fitted' (equipped with automatic brakes) and private owner wagons were

not allowed.

Most general goods traffic was in the form of small

consignments although full wagon loads were sent from factories to other

factories or local distributors. Most bulk goods such as coal and oil were

moved by the wagon load rather than as a complete train of wagons. An entire

train carrying one consignment is called a 'block load' or 'block train' by the

railways. Block trains of coal were run from the mines to docks and to railway

yards where individual wagons would be sent off to merchants, gas works and

factories. A typical block coal train in this period would involve some fifty

or sixty wagons hauled along by a tank engine at maximum speeds of about 25 mph

(40 kph).

The domestic economy was based on the small corner shops and

a great deal of railway goods traffic was therefore made up of small

consignments being sent from one railway station to another for collection by a

local trader. Not infrequently a wagon or van would carry only a single

consignment to a local goods yard, for example half a dozen carpets, hardly a

'full load' for a ten ton van. Traders were given 48 hours to unload a wagon,

paying a fee if they took longer than this. The railway companies managed

something similar, unloading most wagons within a day of their arrival and

loading them up again within another day.

The railway companies advised

the Railway Clearing House (see also Historical Background - The Railway Clearing House) regarding wagon

movements on a daily basis, they had to return foreign companies rolling stock

within five days or pay a daily fee called 'demurrage'. It was seldom possible

to find a return load for a wagon hence there was a great deal of movement of

empty stock.

With the outbreak of the First World War the government

set up an organisation called the Railway Executive to co-ordinate control of

the railway system. Under this system the various companies were still largely

autonomous and overall the arrangement worked very well, about 130 railway

companies were involved and this centralised control lasted until 1921. One

major change introduced during this war was the which dramatically reduced the empty wagon mileage on the

system.

In 1913 the Lancashire and Yorkshire electrified the Bury to Holcombe Brook line at 3500 Volts DC using an overhead supply. Two two-car units were built for this line.

Lancashire and Yorkshire Rly Holcombe Brook EMU

The First World War was a difficult time for the railways, many

of their staff were called up to fight whilst spares and other materials became

increasingly scarce. The general condition of most railway rolling stock

deteriorated during the war and the livery on passenger stock was sometimes

replaced with a plain overall colour (including khaki and black).

The

war brought home the importance of strategic industries and in 1920 the

Ministry of Transport was formed by the government. This new ministry charged

with co-ordinating the development of roads, railways and to a lesser extent

the canals and navigable rivers (legislation relating to deep-sea and coastal

shipping remained the province of the Board of Trade).

In 1921 the

Irish Free State was established giving full independence to the southern

counties of Ireland (implemented in 1922) and the 1921 Railway Act lead to the

1923 government sponsored rationalisation of the railway system known as 'The

Grouping'. This represented a major about face for the Government, they had

lived in dread of the power a railway monopoly would wield and had resisted

amalgamations which they felt would reduce competition. This policy had not

been entirely successful however and three large companies with effective

territorial monopolies had already formed themselves. The North Eastern Railway

was created by the amalgamation of three companies in 1854 giving it virtually

total control in Northumberland, North Yorkshire and Durham, the Great Eastern

Railway formed in 1862 gained unrivalled control of East Anglia, whilst in

Scotland the Scottish Central and the Scottish North Eastern had been absorbed

by the mighty Caledonian Railway.

Amalgamations had been allowed where

these did not threaten a monopoly, mainly smaller lines being absorbed or

leased by larger neighbours, but there remained a great many independent

companies. Scotland and Wales, late starters in the railway business, had both

been opened up by these smaller railway companies. There were also a great many

'Joint' lines, owned or operated by two or more larger companies.

The

`Grouping' of 1923 was in effect a government sponsored rationalisation of the

British railway system. About a hundred and twenty or so of the larger

independent railway companies were amalgamated into four large regional

concerns, subsequently generally referred to as `The Big Four'. These four were

the Great Western Railway (GWR), the Southern Railway (SR), the London North

Eastern Railway (LNER) and the London Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS).

The Big Four were based on geographical regions, LMS being the West of

England, North Wales and West of Scotland, LNER being the Eastern England and

Eastern Scotland, the SR worked the English South coast and the GWR covered the

West of England, South Wales and Cornwall. Naturally there was some overlap of

owned lines, and the provision of running powers on one companies lines for

another companies trains was not uncommon. The GWR and LMS had the strongest

financial position but the Southern Railway companies had been hard worked

during the 1914-18 War. In the East the Great Central and Great Eastern were

both in poor financial straits and even the relatively successful Great

Northern was not as well equipped as it might be. The LMS, LNER and SR were

largely new companies, deriving their operating practice and designs from the

larger absorbed companies. The GWR was slightly different, already a large

company, effectively absorbed all the smaller lines and stamped its identity on

them. The GWR, SR and LNER managed the transition with little administrative

difficulty but the LMS had some trouble dealing with rivalries between the

Midland Railway & the London and North Western Railway in England and

between the Glasgow & South Western Railway and the Caledonian Railway

North of the border .

Each of the new four companies inherited all the

various works built by their constituents but rationalisation concentrated work

at a small number of larger establishments. The main LMS works were at Crewe

and Derby, the LNER had extensive facilities at Doncaster and Darlington and

the SR had works at Ashford and Eastleigh. The GWR had its original massive

works at Swindon, which had been a small village before Brunel decided to use

it as his engineering centre. Each company inherited a number of routes to

London, the LMS operating into Euston and St Pancras, the LNER from Kings

Cross, Broad Street and Liverpool Street, the GWR from Paddington and

Marylebone, and the SR from Waterloo and Victoria.

There were three

large railway companies which had been jointly run before the grouping and

continued as such under the Big Four. Largest was the Cheshire Lines Committee,

linking Cheshire with Lancashire, which had been jointly owned by the Great

Central, Great Northern and Midland Railway. The CLC was unusual in that the

only engines it ever owned were four Sentinel passenger steam rail-cars. The

CLC could not be easily allocated to either the LMS or the LNER and continued

as a separate company jointly owned by these two new companies. A joint the

board of directors was formed, three from the LMS six from the LNER. The CLC

remained as the fifth largest railway company in the UK until Nationalisation

in 1948. In Cheshire after the grouping the CLC, LMS, LNER and GWR all had

lines and complex agreements allowing trains to operate on each others tracks.

From a goods point of view this is one of the more interesting areas in the

country.

The Midland & Great Northern Railway was another joint

operation, this time in Norfolk. Originally operated by the Midland (who

provided the locos and most of the rolling stock) and the Great Northern (who

dealt with the track, signals etc.). This became an LMS/LNER joint company

after the grouping.

The Somerset & Dorset Joint Railway, previously

worked by the London & South Western Railway and the Midland Railway became

an LMS/SR joint line.

The M&GN and S&DJR were both lines which

had a great deal of single track and distinctive operating practices, features

which remained until their closure in 1959 and 1967 respectively.

S&DJR goods rolling stock had been divided between the LSWR and the

MR in 1914, leaving only engineers vehicles, brake vans, the passenger stock

and some locomotives in S&DJR livery. The CLC goods rolling stock and the

remaining S&DJR stock was divided between the owning companies in 1930. The

M&GN rolling stock was divided in 1936, but on the CLC and M&GN the

brake vans and service vehicles remained the property of the joint companies

for some years afterward. Brake vans in CLC livery were still seen around the

country in the 1950's, usually attached to Eastern Region trains.

In

areas such as the Forest of Dean the complicated working arrangements between

the Great Western and Midland Railways on the Severn and Wye Railway were

continued by the new GWR and LMS companies.

As well as the 'Big Four'

and the joint companies there remained a few other independent lines, mainly

'Light Railways'. These continued to operate into the 1930's when economic

conditions forced most into bankruptcy. From a modelling point of view these

would more closely resemble the pre-grouping period in locomotives and coaching

stock. Most goods traffic on these lines travelled in the larger companies

rolling stock.

A summary of the larger constituents of the Big Four is

of use to the modeller as it tells you whether a pre-grouping model can be used

in your preferred company livery. For example the Graham Farish Fish van is a

Great Northern Railway design, which is therefore legitimate in LNER livery. It

is standard practice to define periods in a companies history by the name of

the Chief Mechanical Engineer, or CME. I have included the relevant names and

dates under the company title.

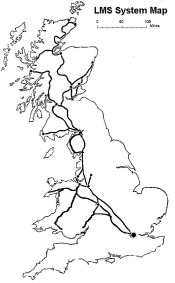

London

Midland & Scottish Railway (LMS)

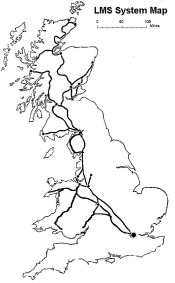

Fig___ The LMS system

CME's: G. Hughes

(who had been CME of the Lancashire & Yorkshire, subsequently the LNWR

since 1904) 1923 to 1925. Sir H. Fowler (came from the MR, where he became CME

in 1903) 1925 to 1931. Sir W. Stanier 1931 to 1944. H. G. Ivatt 1945-1947

Comprised of the Midland Railway (including the London Tilbury &

Southend absorbed in 1912, some narrow gauge lines and some lines in Northern

Ireland), the London & North Western Railway (including the Lancashire

& Yorkshire, absorbed in 1921, the North London Railway absorbed in 1909),

the North Staffordshire Railway (including the narrow-gauge Leek & Manifold

Valley Railway), the Caledonian Railway, Cleator & Workington Railway,

Maryport & Carslile Railway, Garstang & Knott End Railway, the Wirral

Railway, the Stratford on Avon & Midland Junction Railway the Furness

Railway and the Highland Railway.

The LMS also inherited an interest in

certain jointly owned or operated lines such as the Cheshire Lines Committee

and the Midland & Great Northern with the LNER, the Severn & Wye

Railway (operating in the Forest of Dean) with the GWR, and the Somerset &

Dorset Joint Rly. with the Southern (the goods stock of this latter company

being divided between the two in 1930, at which time much of it was still in

S&DJR livery).

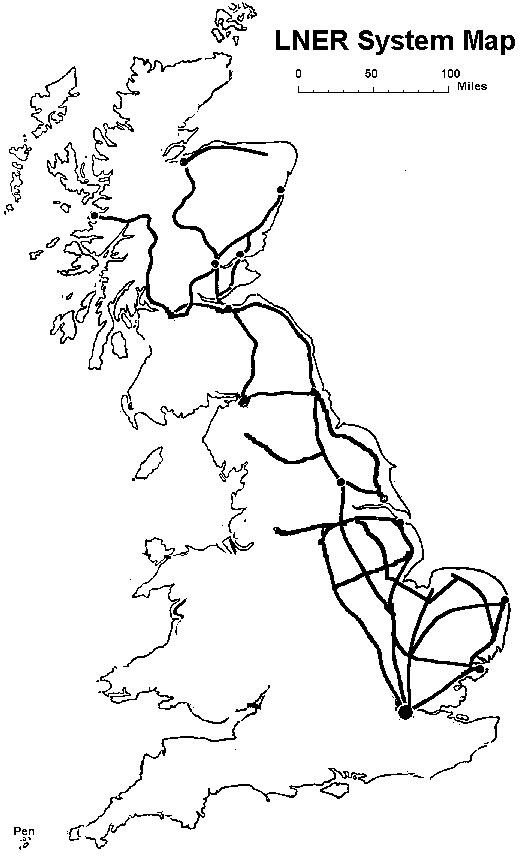

London & North Eastern Railway

(LNER)

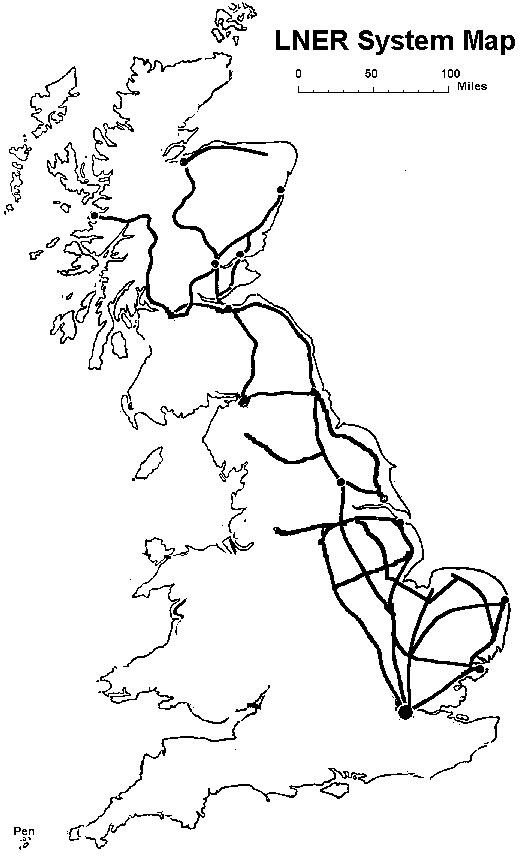

Fig___ The LNER system

CME's: Sir N. Gresley (CME of the G.N.R

from 1911 to 1922) 1923 to 1941. E. Thompson 1941 to 1946. A. H. Peppercorn

1946 to 1947.

Comprised of the North British Railway, Great Central

Railway (called the Manchester Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway until 1897

and including the Lancashire, Derbyshire & East Coast Railway absorbed in

1907 and the Wrexham Mold & Connah's Quay Railway absorbed in 1905), Great

Northern Railway, North Eastern Railway (including the Hull & Barnsley

Railway, absorbed in 1922), Great Eastern Railway, Great North of Scotland

Railway, East & West Yorkshire Union Railway, The Colne Valley &

Halstead Railway and the standard gauge Mid Suffolk Light Railway.

There were 20 or so smaller companies and the LNER inherited interests

in certain jointly owned systems, such as the Midland & Great Northern and

the Cheshire Lines Committee, both with the LMS.

Southern Railway (SR)

Fig___ The SR system

CME's: R. E. L. Maunsel (CME of the

S.E.C.R. from 1913) 1923 to 1937. O. V. Bulleid (who had been the assistant to

the LNER's Gresley) 1937 to 1947.

Comprised of London & South

Western Railway, the Isle of Wight Railway, the Isle of Wight Central Railway,

the Freshwater Yarmouth and Newport Railway, the South East & Chatham

Railway (formed in 1899 by the amalgamation of the South Eastern Rly & the

South East & Chatham Rly), the London Brighton and South Coast Railway and

the Plymouth Devonport & South Western Junction Railway. There were several

smaller companies such as the narrow gauge Lynton and Barnstaple Rly. The SR

also jointly operated the Somerset & Dorset Joint Rly. with the LMS up to

1930 at which time the SR took over operations on this single line route and

the stock was divided between the two grouped companies.

Great Western Railway

(GWR)

Fig___ The post-grouping GWR

CME's: William Dean 1877 to

1902. G. J. Churchward 1902 to 1921. C. B. Collet 1921 to 1941. F. W.

Hawksworth 1941 to 1948.

Comprising the original Great Western Railway

(including the Liskard & Looe Railway absorbed in 1909) to which existing

large network was added several lines in South Wales: The Cambrian Railways

(including the Mawddy Railway), Alexandra (Newport & South Wales) Docks

& Railway Co, the Neath & Brecon Railway, the Rhondda & Swansea Bay

Railway, Burry Port & Gwendraeth Railway, the separate Gwendraeth Valley

Railway, the Llanelly & Mynydd Mawr Railway, the Cardiff Railway, Taff Vale

Railway, Barry Railway and Rhymney Railway. Other constituents included the

Midland & South Western Junction Railway, the South Devon Railway, the

Bristol & Exeter Railway, the Cleobury Mortimer & Ditton Priors Railway

and the West Midland Railway. There were also assorted smaller concerns

including the narrow gauge Welshpool & Llanfair Railway and the Vale of

Rheidol Rly. The GWR was also involved with various joint ownership

arrangements, such as the Forest of Dean railway system with the Midland

Railway, subsequently the LMS and various lines in Cheshire with the LMS and

LNER.

The Vale of Rheidol Railway was allocated to London Midland

Region after Nationalisation and was for a time the only British Railways steam

line. Diesels were introduced for service trains and shunting duties in the

1980's. The VOR was sold to Brecon Mountain Railway in 1988.

With all these companies goods

rolling stock was normally re-painted only as and when it came in for repair,

hence it was possible to see pre-grouping liveries in use on the railways right

up until the outbreak of World War 2 in 1939, rare examples have been reported

as late as 1948.

The 1921 Act also revised the charges for railway

goods traffic, the idea being to simplify what had become an extremely complex

business, this was not entirely successful however. The railway companies were

by this time looking at road transport as a possible avenue of expansion, the

Government ever fearful of monopolies introduced clauses in the 1921 Act which

hindered this line of investment.

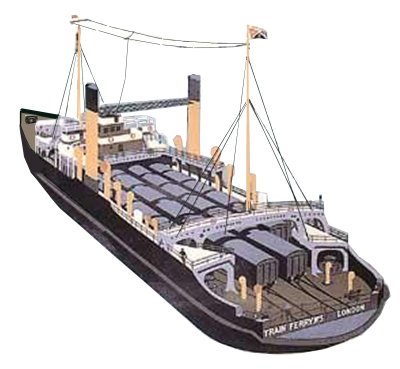

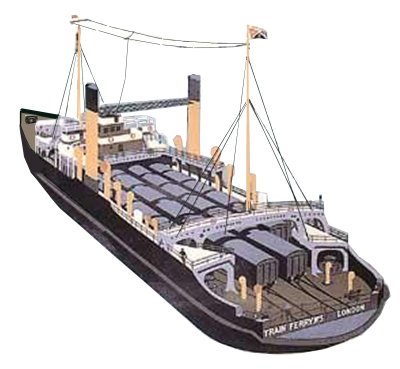

During the First World War the War Department built three ships to carry railway vehicles and established military ports equipped with the necessary docking gear. In 1924 the LNER purchased the three ships and the associated shore 'link-span' equipment from the army, establishing the semi autonomous Great Eastern Train Ferries Ltd. to operate a service from Harwich to Zeebruge in Holland.

Fig ___ LNER (ex WD) train ferry

In about 1926 the railways began

offering door-to-door container services, the containers being transported on

both horse drawn and motor road vehicles at either end of their journey.

Fig___ 3 ton mechanical horse transporting a container

In the deepening recession of the early 1930's the government provided

cash, in the form of low interest loans, to assist the railways and canals with

redeveloping their infrastructure. These loans were used to subsidise several

major improvements to canals, notably on the Grand Union Canal. On the railway

side they were of greatest help to the Southern Railway and the Great Western

Railway, the LMS and more particularly the LNER were not in a strong enough

financial position to make much use of them. This period saw most of the

remaining 'light railways' fail, including several of the Welsh narrow gauge

lines built for slate traffic, a trade which had been in decline for some

years.

It was during the 1930's that the railways began to adopt a more

co-co-ordinated policy for handling goods traffic. Common shared depots were

established and traffic was shared and routed to form more cost-effective heavy

trains. This 'pooling' system reduced the number of smaller goods trains

competing not only with each other but also with the growing force of road

transport.

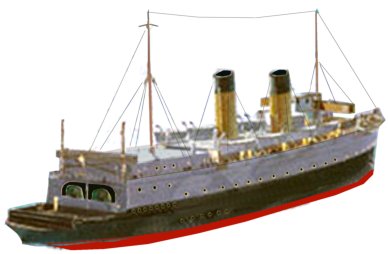

In 1936, the Southern Railway company and the newly nationalised French railway (SNCF) invested in new train ferry docks at Dover and Dunkerque. This service employed three ships each of which could carry twelve international sleeping carriages or twenty four forty foot wagons and an enclosed upper deck had a garage for 25 motor cars. The illustration below is based on a poster produced by the SR advertising this service. Note the funnels are mounted fore and aft rather than at the sides as on the old WD ferries.

Fig ___ 1930s Southern Railway train ferry

By the late 1930's the canal system was in decline but the

railway system, although suffering from road competition was looking quite

efficient. One new trade for the railways was in 'ferry wagons', railway wagons

fitted with securing points to allow them to travel on cross channel ferries or

across the North Sea. The first train ferries had been introduced by the

military in World War One, one former military service between Calais and

Harwich was maintained after the war and additional services soon followed. The

Portuguese were amongst the first to use this system, shipping perishables via

France in special vans with interchangeable axles to suit the standard British

and French and somewhat wider Portuguese tracks. Most goods continued to arrive

in conventional cargo ships however and all docks of any size, and most of the

smaller ones as well, were laced with railway lines.

In 1938 the rivalry between the LNER and the LMS for having the fastest passenger services saw the LNER A4 locomotive Mallard set a world speed record for steam traction of 126 mph (203 kph) in 1938 as it ran down Stoke Bank with a full load of passenger coaches in tow. The photograph shows a model of this engine in its post war British Railways livery.

Mallard

Photo of model courtesy Ian and Sandra Franz

Rearmament in the

later 1930's brought much needed revenue to the railways. In 1939 new passenger

rolling stock for the electrified the Liverpool to Southport line featured

sliding doors, these were the first sliding doors on non-underground stock and

they were not seen again on British coaches until the electrification of the

Glasgow Underground in 1960.

On the outbreak of war in 1939 the

government formally took control of the entire rail network, including the

separate London Transport system and several smaller railways. The general

managers of the Big Four and London Transport were set up as the Railway

Executive Committee to co-ordinate and control the whole railway system. The

railway companies were prepared and the transition to a war footing went

smoothly.

Freight operations increased steadily, stations near military

establishments were suddenly handling ten times the normal quantity of goods,

and by the late 1940 's overall freight tonnage was up by something like fifty

per cent on the pre-war norm. The war naturally brought changes in the traffic,

rolling stock had to be found for these new demands and this often involved

modifications to rolling stock which might be of interest to modellers.

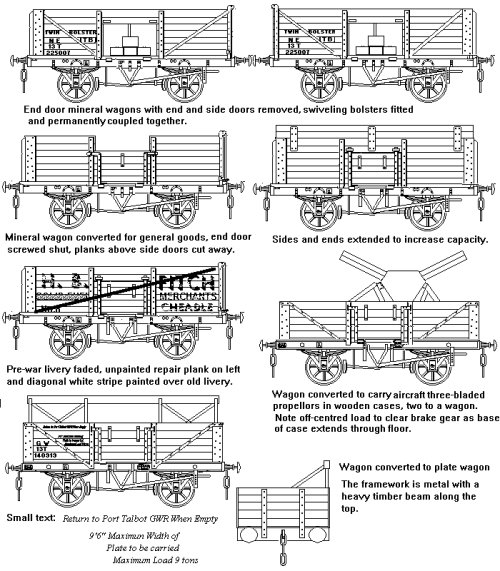

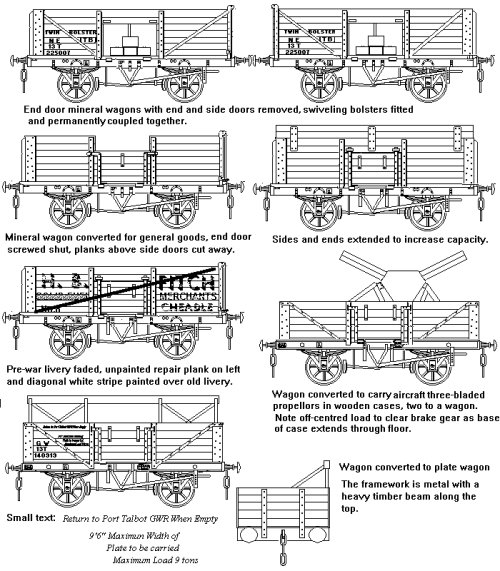

Wartime conversions to goods stock

During this period all the private owner coal and iron ore wagons were

requisitioned and pooled. These wagons could then be seen in any part of the

country. Those with end-doors (Lima & Minitrix) had a diagonal white line,

rising to the end with the door, painted over their original private owner

livery (see Fig___). Private owner wagons for specialised cargo such as salt

and lime was not pooled and nor were the private owner tank wagons.

In

the mid 1940's some additional rolling stock was built, including some 10,000

end-door mineral wagons with steel bodies. Many of these were rebuilds on

existing nine foot wheel base chassis but the design formed the basis for the

post war British Railways standard sixteen ton mineral wagon.

The

railways had a difficult war, the blitz (German bombers raiding cities at

night) caused a lot of damage and locomotives and rolling stock was hard used.

With many of the railway staff in the armed forces, and railway workshops being

used for munitions work, maintenance fell behind. By the end of the war the

railway system was in a generally poor condition, the number of damaged

vehicles waiting for repair had increased by over 60% on the 1939 level. To

compound the problems faced by the railways the government, virtually

bankrupted by the war, was unable to keep its pre-war promise to pay the

railway companies compensation equivalent to moderately successful peace time

year.

Post war nationalisation of the railways was partly a Labour

Party dogma but it was probably unavoidable on economic grounds. The country

had taken a pounding during the war years and the economy was stretched to

breaking point. Railways are capital intensive, that is they require a very

large amount of money to operate at all, they were not providing a very good

return on investment and it is unlikely that investors would have seen the war

weary British railway companies as a worthwhile option. The railway companies

resisted nationalisation but they had little money and the Labour government

was committed. The 1947 Transport Act nationalised the railways, the canals,

the docks and a large proportion of the road transportation systems under the

new British Transport Commission. The thinking behind the structure was based

on the work done by Lord Morrison in forming London Transport; the plan called

for a properly co-ordinated public transport system and it was also intended to

integrate road and rail freight haulage.

London Transport remained a

separate entity but British Railways came into existence on the 1 June 1948,

inheriting a system with about 20,000 route miles of track, serving nearly

seven thousand passenger stations of which nearly five thousand had goods

facilities and a further fifteen hundred pure goods depots. They got about

twenty thousand assorted steam locomotives, only about fifty diesel engined

machines (shunting engines and a few GWR and LMS motor rail-cars) and sixteen electric

locomotives (not including the various passenger electric

multiple units operating in London and on the Southern Railway, in the North East and North West). There were at the time over six thousand private sidings on the

railway system feeding every kind of industry as well as extensive services

into the docks.

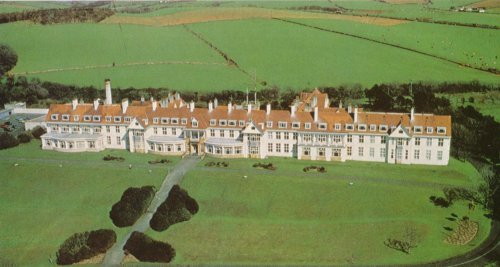

As well as the railway infrastructure British Railways inherited all the assets of the Big Four companies, one important asset was the fleet of ferries, including those carrying railway goods and passenger stock. These became 'Sealink' and remained under railway control for the next thirty years.

Fig___ Sealink cross-channel passenger ferry

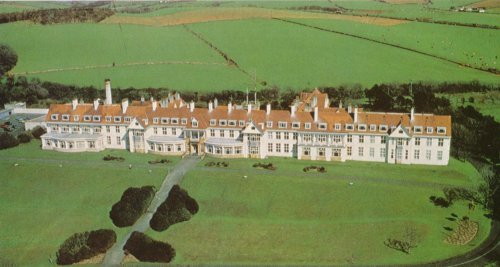

Also many of the larger hotels in the country were railway owned and became part of British Transport Hotels (these remained as part of the system until the 1980s).

Fig___ Turnberry - One of the large railway hotels

The wartime Railway Executive was replaced by a joint

British Transport Commission, with responsibility for British Railways, the

British Waterways Board (dealing with the inland waterways, rivers and canals) and the nationalised road

haulage organisation called the Road Transport Executive or RTE. The operating

arm of the RTE was British Road Services, who painted their lorries red and

their parcels vans green.

Note - Ken Ward, a regular on uk.railways newsgroup advised that the official colours for BRS were: General Haulage - Red, Vans - Green, Meat - Cream, Special Traffic (eg tipper lorries) - Blue.

The BTC was most concerned with the dire state of the

railways and in the event the idea of actually co-ordinating all the various

forms of transport into an integrated system proved too difficult to achieve.

The first British Railways 'crimson and cream' liveried passenger

coaches appeared in 1948. There was still a lot of suspicion amongst railway

workers and various railway workshops suddenly found they had stocks of the old

paint, which of course had to be used up, so coaches and locomotives were still

turned out in pre-war colours for the first couple of years.

Fig___ 1944 Bedford lorry in early BR livery

The railway system

was divided into six 'regions', the former GWR and SR lines were largely

unaffected and simply became Western Region and Southern Region. The LMS and

LNER lines in Scotland became Scottish Region, the remainder of the LMS

becoming London Midland Region. The former LNER lines in England were

subdivided into Eastern Region and North Eastern Region.

Scottish

Region covered the whole of Scotland including the northern ends of the West

Coast Main Line and East Coast Main Line as well as the rail network serving

the industrial heartland of the Central Lowlands between Glasgow and Edinburgh.

Going North they operated the line from Edinburgh via Perth and Inverness to

Wick and Thurso and from Edinburgh, via the famous bridges over the Firths of

Forth and Tay, to Dundee, Aberdeen and Inverness. From Glasgow the West

Highland line ran north to Mallaig and Stranraer served the area as a ferry

port for Ireland.

London Midland Region had two main lines from London.

The main line, which became the West Coast Main Line went via Rugby, Crew (for

the North Wales branch), Preston and Carlisle to Scotland. The second line ran

from St Pancras station in London via Derby, Leeds and then via the Aire Gap in

the Pennines to Sheffield and Carslile. In the later 1960's the LMR took

responsibility for the northern section (north of Aylesbury) of the old GWR

line from London to Chester via Banbury, Birmingham, Wolverhampton and

Shrewsbury. The LMR thus served industrial areas in the Midlands, south

Lancashire, Liverpool Manchester and Glasgow as well as the York, Derby and

Nottingham coal fields. Tourists used the LMR to reach the Lake District and

North Wales and the ferry ports of Holyhead, Liverpool and Heysham brought

traffic from Ireland.

North Eastern Region covered everything east of

the Pennines from the Humber to the Scottish border including the northern

section of the east coast main line (discussed below). With both Hull and the

Tyne ports and the industrial areas of Yorkshire, Durham and Northumberland

this region handled a considerable quantity of heavy freight. The North Eastern

Region was merged with Eastern Region in 1967.

Eastern Region covered

all of East Anglia and eastern England as far north as Doncaster and the Humber

estuary, it operated the East Coast Main Line (discussed below) as far north as

Doncaster. This region also had lines extending from London to Ipswich and

Norwich, the agricultural areas of East Anglia and the important ferry port at

Harwich, which brought continental rolling stock into the UK. The East Coast

Main Line (ECML) runs from London via Peterborough, Doncaster, York and

Newcastle to Berwick where the line continued under Scottish Region to

Edinburgh.

Southern Region has a number of lines radiating out from

Waterloo, Charring Cross and Victoria in London serving Southampton, Brighton,

Folkstone and Dover and (with running powers over the Western Region line) to

Plymouth. This region is noted for the intense commuter traffic in and out of

London but from a freight point of view it had only the industry along the

Thames (notably the oil refinery at the Isle of Grain), a limited amount of

paper and cement and the ferry traffic. There was a small coal field, near

Dover, which was exploited in the late 1950's and 1960's but that generated

little rail traffic.

Western Region operated from Paddington in London

with three main lines radiating outwards. One ran to the South West to Exeter,

Plymouth and Penzance, another ran west to Reading, Bristol and via the Severn

Tunnel to Cardiff, Swansea and Fishguard. The third line went out to Oxford

with branches in the Severn Valley serving Wales with its coal mining valleys.

Bristol, East Shropshire and South Wales were the industrial areas served,

Bristol, Cardiff and Swansea were all important ports and Fishguard had a ferry

service to Ireland.

The first CME of British Railways was Mr. R. A

Riddles C.B.E, however the move toward a national standard series of

locomotives, the devolution of power to the regions and the setting up of the

Ideal Stocks Committee to develop standard rolling stock designs, meant that

the CME's influence was less marked than in earlier years. Generally the

railways continued to operate as before and British Railways accepted delivery

of existing orders for rolling stock placed by the Big Four.

In 1952

the streamlined GWR rail-cars were tried in Lincolnshire and on the

line between Harrogate and Leeds (there had been some earlier trials of these

vehicles on the LNER during 1942). Also in 1952 the first British Railways standard enamelled signs appeared at railway

stations. Each region had its own background colour for these signs;

Midland Region - Maroon

Scottish Region - Light blue

North Eastern Region - Tangerine (Merged into Eastern Region in 1967)

Eastern Region - Light Green

Southern Region - Dark Green

Western Region - Brown (although they did try black as an experiment for Western Region signs).

The illustration below shows a large metal sign set up on the road outside the station and a double sausage 'totem' from a station platforms, both being from Midland Region.

Fig ___ Example of station signs (Midland Region)

During this year there was a terrible storm

with hurricane force winds across Scotland which felled many thousands of trees

between Aberdeen and Inverness. Much of the timber was hauled by road to the

furniture and wooden goods factories in England but the railways managed to get

some of the work. The trees were mainly softwoods such as pine, which grow

straight and have few branches, making them an attractive load for bogie

bolster and bogie flat wagons. A lot of the timber was cut into shorter lengths

in Scotland and shipped in open wagons, these loads resembled pit props (for

which many were in fact sold).

In 1953 British Railways brought back

named freight trains with the reintroduction of the old LNER Green Arrow fully

vacuum brake fitted service for full wagon loads feeding the ports for exports.

The Transport Act of 1953 devolved a lot of power to the railway

regions, for example Western Region was allowed to try diesel hydraulic

locomotives when everyone else was opting for diesel electric's.

In

1954 the 1500v DC electrified 'Woodhead Tunnel' railway route from Manchester

to Sheffield was opened. The sketch shows the co-co passenger engine in the original lined green livery.

.

Fig___ 1500v DC Class 77 Co-Co Locomotive

In 1955 'Pullman' coaches were reintroduced (they had

been withdrawn in 1929), the first lightweight four-car DMU's entered service

on Eastern Region and the government announced plans to allow the railways to

invest in infrastructure.

The original official colours for BR

passenger stock was crimson lower body with cream upper panels. The Western

Region had started painting some of its mainline coaches in essentially GWR

colours in 1953, other regions started using regional colours for main line

coaching stock after the general change in standard BR passenger livery to

maroon in 1955.

A 'Modernisation Plan' for the wholesale upgrading of

the entire railway system was rather hurriedly produced. This plan involved

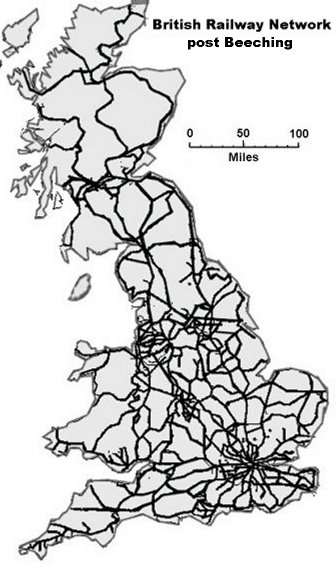

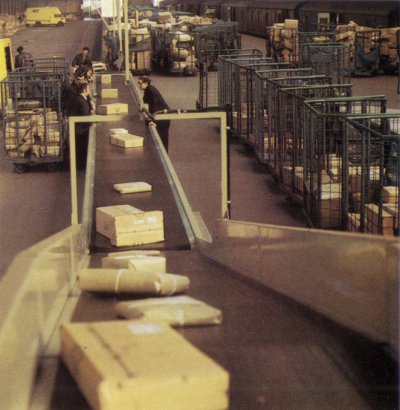

extensive re-signalling based on colour light systems, a shift to diesel and