Private Owner

Wagon and Van Design

As the canal system had evolved in the 18th century the

authorities became concerned about the development of monopolies.

They decided that canal companies should not operate their own fleets

of barges but instead they would operate rather like toll roads,

where the canal company provided the route and charged people for

using it. Hence the 'private owner' barge was the norm on the canal,

which had the additional benefit for the canal company of using the

capital of the private owners to build the barges rather than the

canal company's money.

The system worked well enough on

canals and in the early days of the horse hauled railways everyone

thought they could work in the same way. The Stockton &

Darlington Railway used several private sub-contractors for hauling

both goods and passenger trains. When the Liverpool & Manchester

act was in parliament it was stipulated that private owners could

build lines joining to the main line and operate their own rolling

stock. The widespread introduction of steam locomotives and the

increasing density of traffic on the steam hauled railways made the

'toll road' system unsafe. The 1845 Railway Clauses Act retained the

rights of private owners to operate their own wagons but required all

trains to be hauled by a railway company locomotive.

In the

early years privately owned vehicles were mainly chauldron type

mineral wagons (see Goods Rolling Stock Design - Introduction). These

were usually unpainted wood with the owners name painted crudely on

the side. It was only in the 1860's that more colourful flat-sided

open wagons with the merchants name on the side began to appear. The

mineral wagon dominated the private owner side of the business and

these are considered in detail below. Note that open wagons marked

with the name of a firms product, such as Izal disinfectant or

Cadbury Chocolate, would probably not be for carrying the product but

would be mineral wagons used to supply coal to the factory.

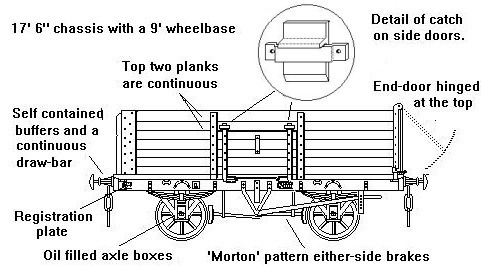

Dumb

buffers were common on private owner stock up to the early years of

the twentieth century. They can be modelled by trimming down the

buffers on a commercial model chassis and building them up with

Milliput. Most early wagons had a hand brake on only one side, often

acting on only one wheel. This difficult to model using a standard

ready-to-run chassis but I have made a few by trimming away the V

hanger and brake handle on a Peco chassis and adding a new brake

handle from 10x20 thou strip. See 'Goods Rolling Stock

Design-Chassis-Buffers' and 'Goods Rolling Stock Design-Chassis-

Brakes' for further information.

The Railway Clearing

House (RCH), originally set up by the railway companies to handle

charges for vehicles wandering onto another company's line,

introduced standard minimum specifications for private owner wagons.

The first significant RCH specification for private owner wagons was

published in 1887 and the Railway companies supported this move by

refusing to accept non RCH standard wagons in their trains. The

second full RCH specification was issued in 1909 and it was this

which required the elimination of dumb buffers (with a time limit set

at 1914 for modification or withdrawal of non-standard wagons). There

were various amendments added to these specifications and the

situation was further complicated by fluctuations in the economy and

various wars. The RCH standards took many years to be implemented and

in the event dumb buffers lasted rather longer than planned.

Not

all 'private owner' wagons were owned by the firm whose name was

painted on the side, the railway companies and the wagon builders all

offered leased vehicles as an option for the less wealthy operators.

Leased railway company rolling stock might be painted with the livery

of the hiring company, although a simple marking 'To be returned to.

. . .' was more common. In the case of seasonal traffic (for example

blankets being shipped to shops ready for the winter) railway company

stock would be used but this might have name boards, or just painted

tarpaulin signs, attached to some or all of the vans.

There

were advantages to owning or leasing your own wagons, for one thing

if your wagon was delayed loading or unloading somewhere you did not

have to pay the railway company for it's hire. The payment made for

retaining a wagon in this way is called 'demurrage'. Some private

owner wagons and more particularly vans stayed in the same place for

a very long time, in effect being used as a temporary store or

warehouse.

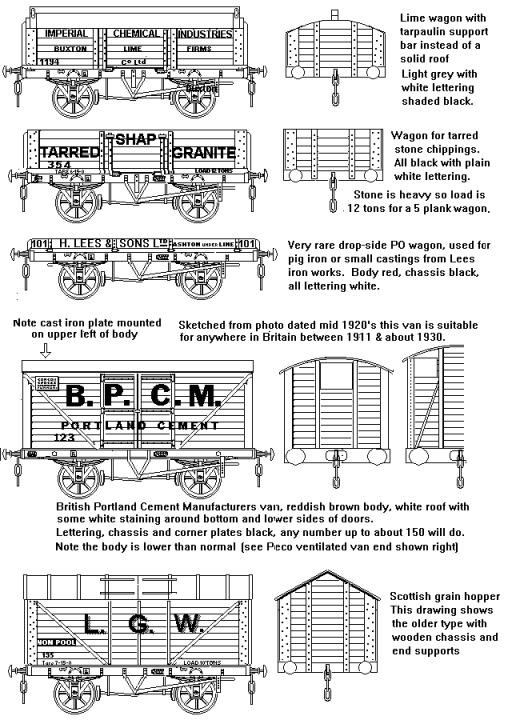

The legislation which defined the railways as

'common carriers' allowed the railway companies to refuse to carry

cargo in its own wagons which might cause damage to the wagon or to

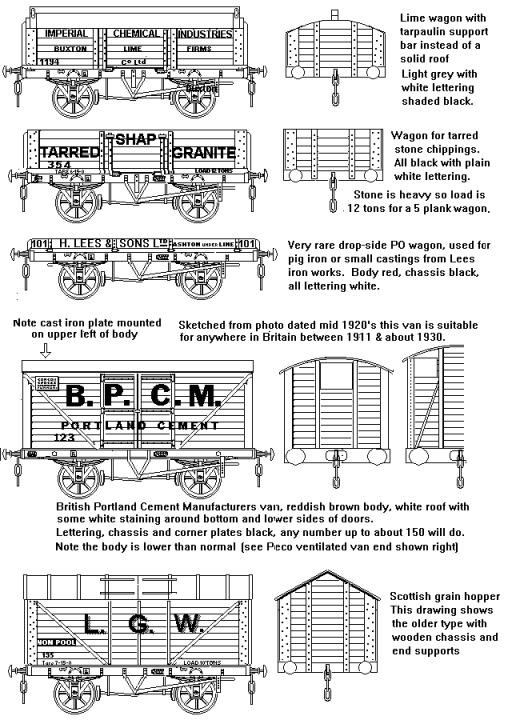

other cargo. A good example of this would be lime. In addition some

commodities might be tainted by carriage with more general cargo, one

example of this being salt. There were therefore quite a number of

specialised vehicles built for the carriage of materials such as lime

and salt. These two commodities both had to be kept dry so wagons

used for this traffic often had house-type peaked roofs (called

'cottage tops' by railway men). Both Peco and Graham Farish offer

roofed wagons suitable for these trades. It should be noted that some

lime and salt wagons did not have a solid roof but instead had raised

ends to support a tarpaulin. The ends could be rounded or pointed but

the latter usually also sported a wooden rail to support the

tarpaulin.

Tar coated stone chippings for road surfacing was

moved in some quantities in the 1920's and early 1930's but this

traffic generally transferred to the roads by 1940. Railway wagons

used for this were all privately owned vehicles with low sides,

typically three planks high or with similar sized iron bodies. The

wooden tarred chippings wagons had steel sheeting added to the floor

to protect the wood from the tar and there would be silvery or rust

coloured streaks visible on the floor after unloading.

Up to

the First World War iron and steel companies operated a number of

privately owned wagons for carrying ingots, forgings and even sheet

and rod. The railways were happy to build stock for this work as the

traffic was regular and profitable so these private owner iron and

steel wagons had largely disappeared by the time of the First World

War.

The private owner vans were rather rare but were often

of interesting non standard designs featuring lower than normal roofs

or even 'peaked' roofs. The main problem with modelling these vans is

that many of the early examples had complex external framing, making

lettering difficult. Up to the 1930's quite a number of outside

framed vans were operated by the South Wales tin-plate companies and

modelling one of these vans, with one suggestion for lettering the

model, has been included in the section on Livery Modification. The

cement companies owned quite a number of the GWR type iron bodied

vans, usually painted in rather complex liveries. They also owned a

number of wooden vehicles as well and some early examples had the

relatively simple BPCM livery. The British Portland Cement

Manufacturers and other cement distributors such as Blue Circle are

discussed in detail in Volume 2 under Cement.

In Scotland

there were several fleets of small (ten or nine foot wheelbase) grain

hopper wagons, two are preserved at the Bo'ness and Kinniel Steam

Railway and one of these forms the basis for a Parkside Dundas

(formerly Westykits) 'OO' kit. Modelling these wagons is discussed in

the section on 'Kit Bashing'.

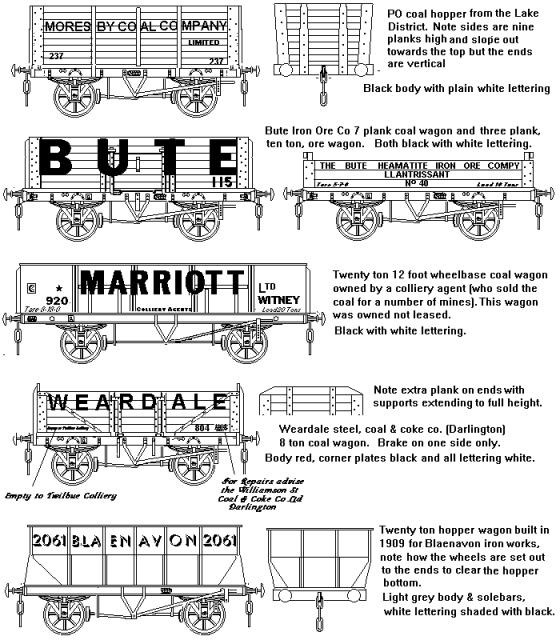

Fig ___ Unusual Private Owner wagons

Fig ___ Models of a cement van and Scottish grain

hopper

Private Owner Mineral Wagons

It is

in the nature of the British railway system that mineral wagons, used

for coal, stone or metal ores, have always outnumbered other wagons

in use. Of these the most common has always been the coal wagon,

millions of which were built.

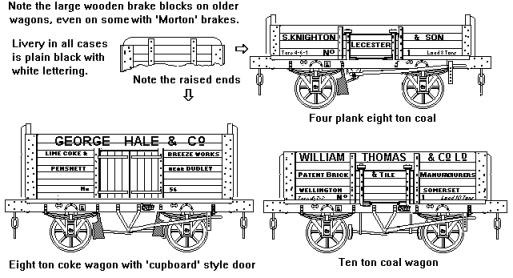

The early coal wagons were of

the chauldron type, a hopper shaped body with spoked wheels and inside

bearings (see Goods Rolling Stock Design - Introduction for a sketch

of one of these wagons). By the 1840's square bodied wooden mineral

wagons were becoming more common although it was not until the 1860's

that these became the accepted standard. At this time the sides of

coal wagons were generally only four planks high and a typical load

was eight tons. Heavy outside frames of timber were still commonly

being used for the wagon bodies but metal reinforcing had started to

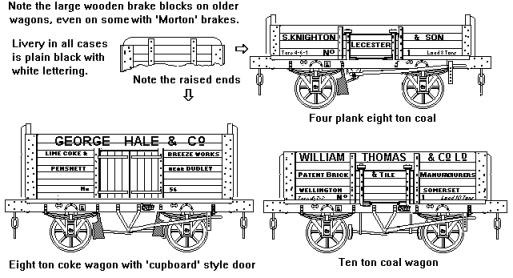

appear. The Morton brake appeared in the 1880's and soon became a

common standard for private owner wagons, early examples retained the

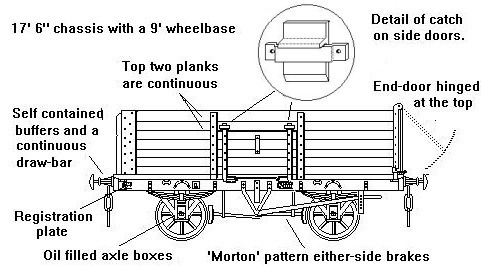

large brake blocks as shown in the sketch below.

Fig ___

Early Private Owner Mineral Wagons

Modelling these wagons was described in Railway Modeller July

2001 (Traffic for Tickling Article 4)

By the turn of the

century coal wagons were built with sides of seven or even eight

planks, capable of carrying a load of up to 12 tons. These were still

outnumbered by the smaller four and five plank wagons which had a

capacity of perhaps eight tons each. Collieries and larger concerns

favoured the larger wagons, local traders preferred the smaller

vehicles. Prior to the First World War it was not uncommon to see

raised ends on private owner coal wagons. The owners would try and

rent their vehicles out for other traffic during the summer months

and the raised ends were provided to support a tarpaulin. By the

later 1920's very few private owner mineral wagons were built with

raised ends, reflecting their abandonment on general goods wagons by

the larger railway companies.

On mineral wagons the top one

or two planks were usually continuous above the drop-down side doors.

Generally the five plank coal wagons had both ends fixed but some of

these and many of the 7 or 8 plank wagons might have one or both ends

fitted with a door hinged along the top edge. In Scotland some wagon

builders favoured cupboard style double doors in the sides and

vertically planked end doors, with heavy timber external frames, the

LNER inherited quite a number of this kind of wagon from the

pre-grouping companies. The end door was hung from a timber beam

rather than a metal rod, supported by metal hoops attached to the

framing on the door itself. These can be produced from the Peco five

plank wagon with a bit of carving, but they were rarely seen south of

the border.

Fig ___ Scottish designed wagon with cupboard

style side doors and vertically planked iron hooped end door

Modelling

these wagons was discussed in Railway Modeller July 2001 (Traffic for

Tickling Article 4), the livery shown is for a fictional light railway

Elsewhere drop-down side doors and

horizontal planked end doors with metal strips were the norm. Wagons

with end doors could be emptied by tipping them up but the method of

tipping these 'end door' wagons depended upon the location. In some

cases this involved a hinged section of track or the wagon might be

emptied into a barge or ship by lifting it bodily with a crane or

hoist. The maximum angle a wagon could be tipped was about forty five

degrees, any more than this put unusual loading on the axle bearings

(see Volume 2 Fig ___).

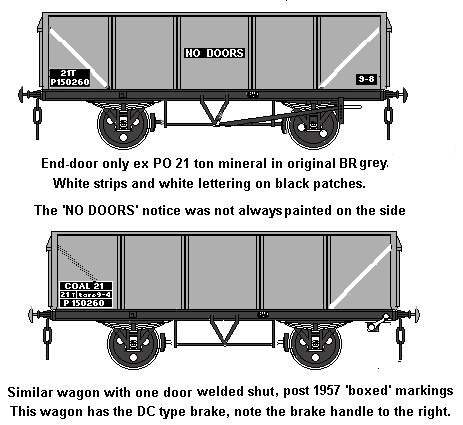

The end fitted with the door was on

railway company stock usually indicated in some way. The Midland

Railway and in the early years is successor the LMS used a white

vertical stripe on the wagon side at the end with the door. By the

late 1920's by a diagonal white stripe on the side became the norm

for all companies although the size and location of the stripe varied

somewhat. Some wagons were built with only an end door and no side

doors, some of these wagons had end doors at both ends. These were

used for supplying larger consumers such as electricity generating

stations or for the docks in South Wales, where wagon tipping

facilities were the standard method of emptying the wagons.

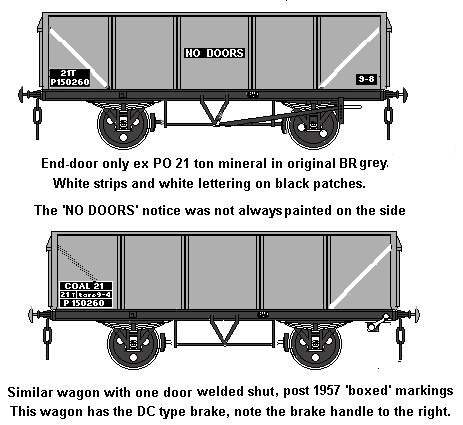

Fig

___ Ex Private Owner end-door only steel wagons in British Railways

livery

Mineral wagons also often had bottom doors, to allow the

load to be emptied through the bottom. Bottom doors were usually

indicated by a shallow open V symbol, something on the lines of \ /

painted near the bottom on the side of the wagon. Details of all such

markings are considered separately under Liveries. If the wagon's

side door was damaged these bottom doors could be used to empty the

load onto the track underneath, the coal then being shovelled out by

hand.

Private owner coal wagons presented several problems

for the railways. By the nature of the trade half the wagons would be

empties being returned to collieries and because of the government

regulations on charging these brought in very little revenue. Their

low capacity meant they occupied a disproportionate amount of siding

space and they were often poorly maintained and many of the private

owner wagons were old and poorly maintained. The grease filled axle

box was virtually standard on privately owned rolling stock but these

grease boxes tended to dry out, causing fires and sometimes melting

the ends off the axles. Wagons of this type had to have their axle

boxes inspected frequently when in transit. There were various

attempts to rationalise this situation, the Midland Railway made a

serious attempt to buy up all the private owner rolling stock on its

lines, but they found they couldn't afford the exercise.

From

the 1880's various experiments were made with higher capacity mineral

wagons, mainly by the railway companies themselves. The Caledonian

Railway up in Scotland built some large bogie coal wagons at about

this time.

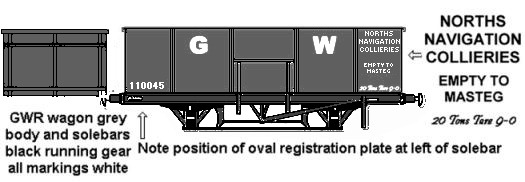

Only the railways of the North East made extensive

use of hopper wagons for coal although they had to provide coal drops

or ramped discharging bays for hoppers in their goods yards. The

North Eastern Railway actively discouraged private owner coal wagons,

offering instead a range of four wheeled wooden bodied hoppers of up

to twenty ton capacity for lease to coal traders at preferential

rates. There were some private owners who still preferred to operate

their own wagons even under this regime and they built hopper wagons

of a broadly similar design (see Fig ___). Other companies tried

similar schemes and the GWR followed the example of the North Eastern

by building rolling stock itself and offering preferential rates for

people leasing these wagons. They built large numbers of 20 ton four

wheel wagons on a twelve foot wheelbase with oil axle boxes from

about 1900, these were iron bodied with curved corners and early

versions had no end doors. The same basic design was developed,

adding square corners in about 1918 and they were built with doors at

one or both ends and either one or two doors on either side. The 20

ton wagons required something like a third less siding space for a

given quantity of coal and they had fewer axles for a given load, so

a loco could pull a larger payload. The drawbacks were the poor

quality of many colliery lines, restricting the maximum axle loading,

and the cost. In 1923 the GWR's Felix Pole introduced a thousand 20

ton end-door wagons to be leased or sold on hire-purchase to the

larger private owners.

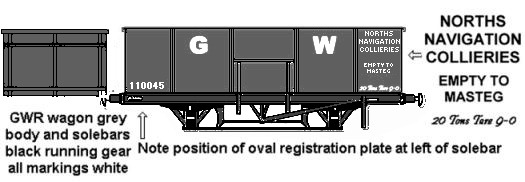

Fig ___ Felix Pole 20 ton coal

wagons

By the early twentieth century there were about half a

million private owner coal wagons on the system, typically of seven

to ten tons capacity and usually fitted with grease-filled axle

boxes. In 1920 the Railway Company Association suggested a standard

for a seven plank coal wagon of 12 tons capacity with a 10 foot wheel

base which formed the basis for the Railway Clearing House standard

specification of 1923, but the older wagons continued in use for many

years.

Fig ___ RCH 1923 Standard Coal Wagon

Converting a Peco mineral wagon to an end door type was

described in Railway Modeller March 2001 (Traffic for Tickling

Article 2)

Coal exports stopped during the First World War

and many of these trades never resumed. With the General Strike of

1926 and the general depression in the 1920's and 1930's domestic

demand for coal slumped and investment was scarce. In spite of this

more of the 'Felix Pole' wagons were built using the government low

interest loan scheme in the 1930's and by the outbreak of the Second

World War there were over five thousand GWR built twenty ton iron and

steel coal wagons on the system.

Smaller private owners in the

main stayed with the older wooden bodied stock, often retaining

grease filled axle boxes. The generally poor quality and capacity of

the private owner fleets was a matter of some concern from a safety

point of view and in 1919 the Ministry of Transport Act obtained

powers to restrict or prohibit the use of private owner wagons on

railway company lines. In the event these powers were never used,

mainly because of external economic factors such as the strikes of

the 1920's and the depression of the 1930's.

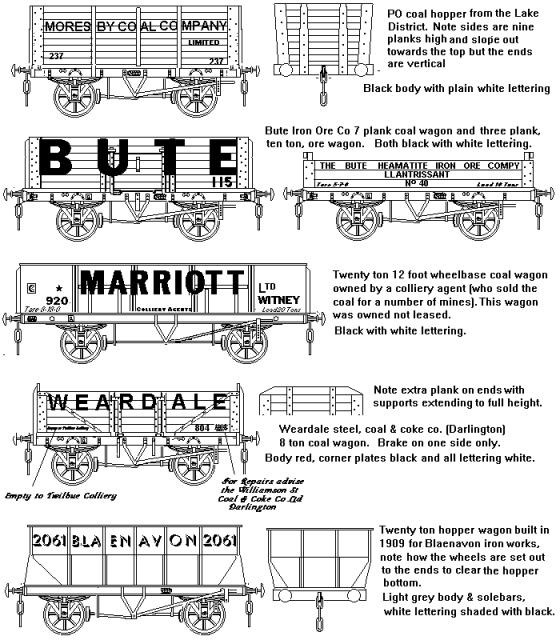

Not all private

owner mineral wagons were standard wooden bodied types, as well as

the various steel bodied wagons there were also hopper wagons in both

wood and steel but these were only operated by larger companies. Also

not all mineral wagons were for carrying coal, the iron and steel

industry built a number of mineral wagons for carrying ores, these

are low value cargo and hence of less interest to the railway

companies. The steel twenty ton hopper shown in Fig ___ was built in

1909 and was used for iron ore traffic.

Iron ore required low

sided wagons to keep the axle loading on a four wheeled wagon within

the permissible range, it was also moved in hopper wagons, fitted

with relatively small metal hopper bodies. The model shown in Fig ___

was built using a body from a Graham Farish open hopper wagon, full

details on modelling this wagon have been included in the section on

Kit Bashing (see Fig ___). These private owner ore hopper wagons were

never commonplace and would have operated on very restricted circuit

workings between the mine and the iron or steel works.

Fig

___ Unusual Private Owner Mineral Wagons

Stone, again a heavy and dense material, was moved in

low-sided wagons. Large blocks of stone were often carried on one

plank open wagons, dressed stone would travel in one or three plank

wagons and broken stone or 'road stone' usually travel led in three

or five plank wagons although this latter material was not a common

cargo prior to World War Two.

China clay, shipped as a thick,

wet, white sludge is also heavy and the areas in which china clay was

found there were some private owner 1, 2 or 3 plank open wagons built

for this traffic. These tended not to travel very far, running mainly

between production centres and river or canal wharves where the clay

was loaded into barges or small coastal sailing ships. The GWR, which

moved most of this traffic, built about a thousand special five plank

open wagons for this traffic in the late 1920's. Modelling the

china clay wagons was described in Railway Modeller May 2001 (Traffic

for Tickling Article 3. The conversion is simple, carve and scrape the supports from one end of the body, scribe in the planks acros the ends, add a rail of 20 thou rod across the top of the end and add three vertical straps (up the end and bent over the top of the rail) from 10x20 thou strip or strips of Bacofoil. You can also add three longitudinal strips of Bacofoil to the floor of the wagon, shiny side down, to represent the zinc sheets added to reduce rot from the wet clay.)

Fig___ GWR/BR china clay wagon model

When

war broke out in 1939 well over ninety percent of the private owner

rolling stock consisted of coal wagons. During the war all these

private owner mineral wagons (not including specialised stock, such

as tar tanks, lime, salt and cement wagons) were requisitioned by the

Government and formed into a common pool. After the war British

Railways bought these mineral wagons from their previous owners,

paying compensation based on the capacity of the wagon and regardless

of condition (sixteen pound ten shillings for an 8-ton Private Owner

wagon). Some new private owner mineral wagons were built just after

the war but there were not many of these and with British Railways

policy of moving coal in its own wagons they had all been withdrawn

from service by the early 1960's.

In about 1952 the older,

low capacity wagons with grease axle boxes were all burned, a few of

the more modern wooden bodied wagons and many of the steel bodied ex

private owner wagons remained in British Railways service into the

1970's. There were many privately owned railways however, collieries,

docks and larger factories. These continued to use their own, often

elderly, rolling stock for many years and wooden bodied coal wagons

operated into the 1980's in docks and collieries.

Considering

the private owner wagons on offer the five plank wagons would mainly

have been private traders wagons. The seven plank mineral wagons were

favoured by collieries in the South Wales coal areas but the eight

plank type seems to have been more common in the Midlands and North

East coal fields. Minitrix offer an eight plank end door wagon, Lima

had a seven plank model (which looks better on a Peco ten foot

chassis) and P D Marsh offer a white metal kit of a seven plank end

door type. Peco have released a seven plank end door wagon as a kit

running on their nine foot wheelbase chassis and any layout set

before the 1970's should have a number of these. The Peco and Graham

Farish seven plank wagons have no end door, but the Peco five and

seven plank wagons can be modified to end door types. This was

described in Railway Modeller March 2001 (Traffic for Tickling

Article 2).

The Minitrix chassis used on their eight

plank and steel bodied coal wagons is of a 'fitted' type with clasp

brakes but virtually all private owner stock was unfitted so for

accuracy one should remove the outer brake shoes on the Minitrix

chassis. If you feel up to it you could try carving away the vacuum

cylinder as well, but that would be difficult. Alternatively you can

swop bodies with a Graham Farish single-vent van, which was more

likely to have such a brake. Most of the pre 1940 vans would not have

had the tie-rods between the wheels but some did have them and they

are tricky to remove neatly.

^

Go to top of page

International Good Guys ~ Making the world a better place since 1971 ~ Site maintained by

All material Copyright © Mike Smith 2003 unless otherwise credited