International Good Guys ~ Making the world a better place since 1971 ~ Site maintained by

All material Copyright © Mike Smith 2003 unless otherwise credited

| Return to Appendix One Index |

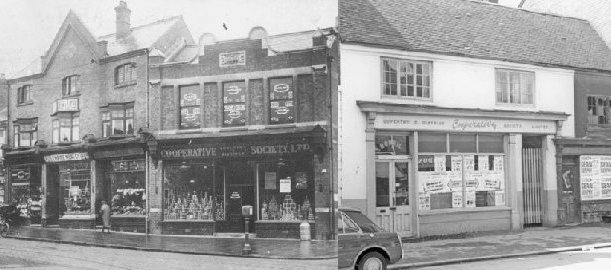

Almost any building can be a Co-Op, they didn't have a particular house-style. Most were victorian terraced shops with the name of the local co-op society painted above the door. The later purpose-built central Co-Ops were often paladian in style with mock bell-towers on the corner. Many of these were destroyed in WW2 and replaced with single-storey temporary wooden structures of which few if any pictures survive. The post-war Coventry Co-Op was built in so-called "Festival of Britain" style with an ornamental concrete frontage to match the civic theatre opposite. This was later remodelled in a less distinctive style. An extension to the same building is Georgian to blend with a side street which no longer exists.Kim also supplied a number of photographs with captions -